MOCO360: Forty-six hours before his football team kicks off a new era, one that its fans hope will erase a quarter century of miserable memories, Washington Commanders owner Josh Harris—a lifelong fan himself—is sitting in a room on the third floor of Planet Word, the downtown D.C. museum dedicated to language. Hundreds of words, stacked 22 feet high, cover one of the walls. Among them: belief.

A native of Chevy Chase, the 58-year-old Harris is a former wrestler who has always believed in the power of sports to unite, which is why he pivoted to the world of sports after making a fortune in business. In 2011, he bought the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers, and his sports and entertainment company has gone on to add the NHL’s New Jersey Devils, part of the British soccer club Crystal Palace, and a host of other venues and smaller teams to a portfolio that also includes the NFL’s Commanders, which he purchased in July for a record $6.05 billion.

Harris waits to walk across the street to Franklin Park for a season-opening pep rally for fans who have put their faith (another word on the wall, located right next to greedy, which has been used more than once to describe the guy Harris bought the team from) in him and his all-star ownership group of minority partners—which includes Montgomery County magnate Mitchell Rales and NBA legend Earvin “Magic” Johnson. He’s contemplating what those first moments in the FedEx Field owner’s box might mean to him.

“I’ve owned sports teams, and this feels like a playoff game to me,” says Harris, whose Sixers and Devils have made postseason runs. “A lot of work has gone into getting the team prepared for opening day and also getting the stadium prepared. Thousands of details. I feel tremendous anticipation and excitement.”

The son of an orthodontist and a teacher, Harris attended The Field School in Washington, D.C., before earning a bachelor’s degree in economics from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. He went on to Harvard Business School, where he met his wife, Marjorie (they have five children together), and at the age of 25 co-founded the private equity firm Apollo Global Management. Forbes estimates his net worth at $6.6 billion.

Despite all his success, Harris still yearns for competition.

“Sports has been a triple play for me,” he says. “Being around the best athletes in the world, giving me an avenue to compete. As I get on to, let’s say, my more mature years, being able to help a city is very important to me.”

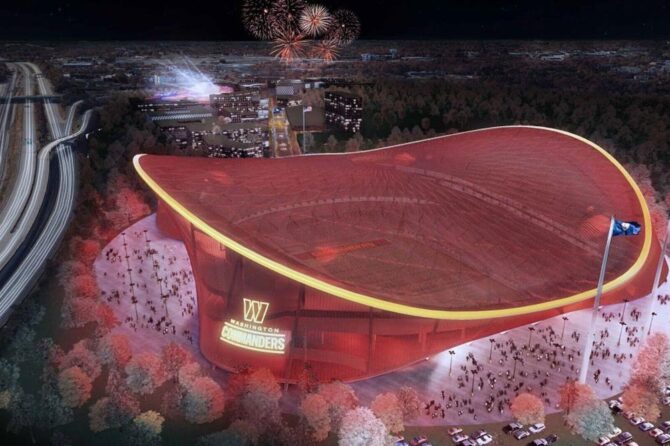

Chief among his long list of priorities is finding a new home to replace the reviled FedEx Field. Although the team spent $40 million on upgrades to the stadium before the season, remaining there is not in the long-term plan. Under former owner Dan Snyder’s reign, Maryland, Virginia and the District showed little appetite for luring the team, but now that Harris has taken over, that seems to have changed. If he’s able to turn around his beloved once-proud franchise, he will become a hero in his hometown. That’s the dream—which is one of the bigger words on the wall.

We spent 45 minutes talking to Harris on that Friday afternoon in September before the regular-season opener. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

As an owner, when you watch your team play, can you just be a fan? Or do you always have a million different things running through your head?

It’s like being a fan on steroids. It’s turbocharged. I can only compare it to when I was just a fan versus now. My emotions are much greater. At the same time, you’re hosting literally thousands of people. You have to be available to a lot of different people. When you win a big game, the elation that you feel is incredible. When you lose, I get into a bad mood. What I do now, because it’s not fair to my family and other people that are close to me, I become a little more stoic. I give myself a little time to get over it. I try to not show it on the outside. When you’re at the game, obviously people are watching you, and so I feel a lot of stress. The players are playing the game so there’s not a lot you can do about it, so you need a little bit of training to keep your emotions on the inside.

Were you a big sports fan growing up?

I was all in on sports. We missed the Senators, so we would go down to Memorial Stadium and watch the Orioles. There were no Nationals. I was there when the Capitals came. We were there for the opening of the Washington Bullets in Landover at Capital Centre. But the dominant sport in Washington always was football. That was the sport that, by far, we mostly focused on.

Do you remember your first game at RFK Stadium?

I do remember being at RFK as a really young person, walking down East Capitol Street. I remember walking in, feeling the noise, and hearing the fans roaring and cheering. I remember looking up at [then-owner] Jack Kent Cooke’s box. It was an amazing place.

What was it about the franchise in that era that you so respected and admired?

It was always a winning franchise. It was a uniter of Washington. I had this amazing year in 1982-83 when I saw the Red— the Commanders—I almost slipped up—beat Dallas, and then that famous John Riggins run on fourth and one [to win Super Bowl XVII]. For me, sports was always very important, and the Commanders always stood for unity and winning and values.

You were a wrestler growing up and in college. The wrestlers I’ve known speak about the sport in almost spiritual terms. What is it about wrestlers that sets them apart?

Wrestling changed my life in terms of the discipline and intensity that it brought to who I was as a person. In wrestling, you go out on the mat and it’s you against another human being. They’re trying to drive your head into the mat and dominate you physically. There’s nowhere to hide. It’s a combat sport. There’s nothing like the experience of getting physically dominated as a learning experience to then say, ‘I didn’t like that. I don’t want that to happen again. How can I avoid that happening again?’ That’s about running and lifting and training and practicing and putting a tremendous amount of grit and tenacity into your lifestyle and who you are as a person. Wrestlers tend to over practice. They tend to constantly work, condition. No one’s ever accused me of being outworked. It pushes you to your absolute limit. You’re exerting 120 percent of your being, of your soul, to survive. There’s no one that’s going to help you but you. Life is tough, so you have to prepare and be ready for it.

You went to the Wharton School at Penn and then on to Harvard Business School. What attracted you to the world of business?

My dad had been an orthodontist. My mom was a teacher and then a homemaker. I knew absolutely nothing about business. I went to Penn and I took an econ class and I really liked it. Then I found out there was this school called Wharton, which turned out to be the best undergraduate business school in the country. I said, Wow, maybe I should do that. I found my calling early as an investor. A lot of people are blessed with innate skills. I was blessed as an investor and a business builder. I remember senior year my dad saying, ‘You should be an accountant; that’s really the safe way to go.’ I said, ‘No way.’ I went to Wall Street.

That was the top of the food chain in terms of where the best and the brightest people wanted to go. I went to a place called Drexel Burnham Lambert, which at that point had created the high-yield market. I went to this thing called the Financial Analyst Program, which is like a boot camp for finance where you work 100 hours a week but you learn about the most interesting deals with the smartest people. At the end of that two years, I said, ‘I’m going to apply to one school, and if I get in, I’ll go; otherwise I’m going to keep working.’ Harvard Business School let me in. I always kept shooting above. With young people I always say, ‘Shoot for the moon; shoot for the stars. Dream big. Even if you miss, you’re going to be better off.’

Why did you decide to get into sports?

When I look back on it now, something inside of me was very moved by sports, both in terms of my personal affinity to playing it—later in life I did marathons and triathlons, and I’m still very into fitness—but also the sort of common purpose and the shared experience that sports gives a city. Deep in my memory—I didn’t know it at the time—was this notion that sports brings people together. I had heard that the Sixers might be for sale. The Sixers hadn’t won for a long time and had lost a little bit of their way. They were losing a lot of money, and the city had gotten tired of them. I called them, and then 18 months later I led a group to buy the Philadelphia 76ers. They were between 25th and 30th in the league in terms of revenues.

We rebuilt the Sixers and we won more than 50 games the last five seasons. We love Philly. They are sports passionate and they have supported the team, and they are constantly holding us accountable in many ways. We are a championship contending team. We haven’t quite pushed through yet, which creates frustration for everyone, most of all me. But we’re right there. We have to slay the leprechauns at some point: We have to beat the Celtics.

How involved in on-the-field/court/ice personnel decisions are you?

I believe in hiring and retaining and motivating and holding accountable the best coaching staff and front office people, and then trying to support them through organizational building. And creating edges relative to competition around the league. Obviously, players win championships. Owners don’t win championships. Player selection, game strategy, player health and safety, all that stuff is advancing scientifically very quickly. We’re on the cutting edge of everything in terms of trying to support the franchises.

I’ve been doing a bunch of that here already in terms of looking at how we can support [head coach] Ron [Rivera], [executive vice president of football/player personnel] Marty [Hurney], [general manager] Martin [Mayhew] and their staff as to the analytics, player health, sport science. We’re starting to make some strides in our thought process. You’ll probably see some new people showing up soon.

As far as being involved, I think on really big decisions that are millions and millions of dollars that are franchise-changing decisions, I’m of course going to be involved. On smaller decisions, I like to be briefed, I like to see how people are thinking, but I’m not going to micromanage.

What did you find most surprising or disturbing about the way things were done with this franchise once you took over?

The franchise was in need of significant investment. In the stadium, everything from plumbing and leaks and bathrooms to sound systems, ovens. On the football side, it’s the same thing. There’s a lot of things to do here. On the sports side, it’s a tent for the players’ families, it’s Gatorade stations, it’s extra hot tubs so the players don’t have to wait for them and can get home. Dozens and dozens of small items.

The interesting thing to me also was that the players had noticed that in their own stadium sometimes there were more opposing fans versus home fans. They said, ‘We really appreciate you being here because we think that now our stadium’s going to feel like a home field.’ That was really surprising to me.

What do you feel your role is in terms of rehabilitating the team’s reputation in the community and within the league?

I want the team to be something that my kids can be proud of, that the city can be proud of, that fans and their kids can be proud of. That’s how I’ve tried to live my own life. I want it to stand for excellence and integrity, and so we’ve come in very quickly and sent that message. We’re asking a lot of the business staff and certainly the front office and the coaching staff and everyone. To build a championship contending team, you need to pace everything up.

In sports, when you own a franchise, it’s very different than business. The public holds you personally accountable. There’s so much publicity that people expect you, as the managing partner, to be accountable for the organization. That’s a huge responsibility that keeps me up at night because life is complicated. Things happen. You do your absolute best, but I spend a lot of time thinking about how do we set this thing up so we stand for integrity, excellence, inclusion, diversity. I’m proud to say that the team and [president] Jason [Wright] have done an amazing job. Ron and his staff have an incredibly inclusive organization. We’re upping everyone’s game, but it’s a bumpy road. It’s not a straight line.

Obviously there’s been a lot of talk about a new stadium. What are a few of your favorite stadiums or arenas, and what qualities do they share?

I always start with football and winning games, because no matter what else we do, if we’re not successful at that, we’ll be judged harder. If we’re successful at that, it’s easier. I think RFK was a place where if you were coming in as an opposing team you didn’t want to be there. So it was like an extra man on offense and defense. I was talking to Troy Aikman, and he said, ‘I didn’t like to go in there.’

You want that, and then you want a place that’s accessible, that’s inclusive, and where the fan experience is elevated. That’s a complicated mosaic. Really big picture is creating positive economic activity for places that might need it. Building a stadium in

Newark [New Jersey], building our [Sixers] practice facility in Camden [N.J.], building where we’re attempting to build in Philly, these are all things where we’re helping thousands of people and using contractors from diverse backgrounds. We’re really focused on how do we create economic activity in the right places. The overall goal would be to do all of that. Obviously, it’s going to take some time to figure out.

Let’s talk about nicknames. I’m not going to ask you about changing the nickname, but what are the components that make up a good nickname?

Look, right now we’re really focused on football, the fan experience and engaging with the city. Right now we’re focused on avoiding distraction, and we’re all behind the Washington Commanders.

Sports is a very zero-sum game, but in your first year, aside from wins and losses, how are you going to judge the success of the season?

Certainly everyone’s always going to judge wins and losses, and that’s the way it should be judged. We got here at training camp, so the reality of it is our ability to affect that [this year is minimal]. We think Coach Ron is a good leader, and we’re very excited about the season. The other components are going to be: Have we created engagement with the city? Have we started achieving change on the narrative? Have we started to make this team something that people are proud of? Have people started reengaging? Are there more home fans than away fans at our games even when we play the Giants? …I’m not going to mention any other teams. I don’t want to get myself into trouble (laughs).

Do we own that noise? And then, have we improved FedEx Field? Have we started to make strides in the community in terms of helping people? Have we started to make some progress on our thought process around the next venue of the Washington Commanders?

You and your wife, Marjorie, founded Harris Philanthropies in 2014. What’s your philosophy when it comes to philanthropy?

My grandfather was a U.S. postal worker from Philly. My other grandfather was an appliance repairman. Their parents left Eastern Europe to avoid religious persecution and came through Ellis Island. My dad and my mom went to college, the first in their families. And now here I am, and I’ve experienced tremendous success through business. I always look at it as if someone paid it forward, someone gave me the opportunity to have this, and so I look at my life as I have a finite amount of time. I’m religious. My job is to make the world a better place and impact the most people as quickly as I can.

We’re big investors in after-school sports. Backing entrepreneurs. Basic financial literacy. Then we do health and wellness for communities in need. Education. We gave the largest gift to the [Philadelphia] Police Athletic League in history.

It’s super exciting for me to be able to come home to the area where I grew up and be able to help people.

Do you spend much time in Montgomery County these days?

Well, my mom still lives in Friendship Heights. I went and visited my old house in Chevy Chase. I just knocked on the door. It’s right near East West Highway and Beach [Drive]. It looks similar. I grew up in a three-bedroom house, two levels on a quarter acre.

I just knocked on the door and they answered. We had a long discussion. It was pretty funny.