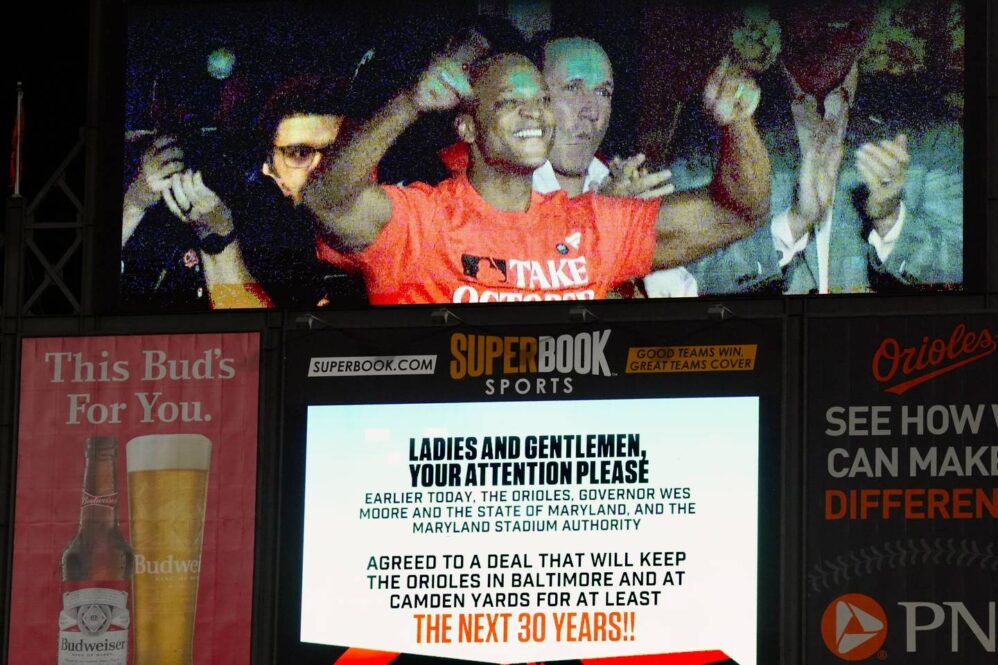

BALTIMORE BANNER: Officials from the Baltimore Orioles and the state government unveiled the outlines of a future lease for the team at Camden Yards with great fanfare this fall.

We know the two sides have agreed in principle on a number of terms for the ballclub to remain at the state-owned Oriole Park at Camden Yards: The term would be for 30 years, the team would pay no rent but take over routine operations and maintenance costs, and the team would be allowed to redevelop areas including the B&O Warehouse, the Camden Station building and a strip of parking lots between the warehouse and train tracks.

But many questions remain about the agreement, which for now is memorialized in an eight-page memorandum of understanding — not yet a legally binding lease.

The current lease expires on Dec. 31, and both sides aim to work out the details and have an actual lease signed before then. The lease will need approval by the Maryland Stadium Authority’s board of directors and the state’s Board of Public Works.

Here are issues we’re watching as the end-of-year deadline looms.

Will a lease be done by the Dec. 31 deadline?

Publicly, Gov. Wes Moore has said there will be no extension needed. As recently as Monday, he said during a speech in downtown Baltimore: “We’re proud of the fact that we’re now finalizing an agreement that is going to keep the Baltimore Orioles here for 30-plus years here in the city of Baltimore. No short-term deals.”

But there are a lot of legal and financial details yet to work out. The MOU allows the current lease to be extended “as reasonably necessary so as to accommodate the schedule for finalizing all such documents.”

The stadium authority board typically meets monthly, but seems to be willing to hold additional meetings as needed. The Board of Public Works, meanwhile, has a fixed schedule of one to two meetings per month, with its final 2023 meeting planned for Dec. 13.

How will private redevelopment work?

The memorandum of understanding includes a provision that the Orioles would be granted a 99-year ground lease on part of the stadium complex, with the idea that it would be redeveloped.

The area in question, according to the MOU, includes everything on the Camden Yards complex north of Lee Street: the ballpark, the B&O Warehouse (currently used for state and private offices, with a retail store, betting lounge and ticket office on the ground floor), the vacant Camden Station building and a strip of parking alongside the warehouse down to Lee Street.

Orioles Chairman John Angelos has described a “live, work, play” vision in broad terms, but we’ve yet to hear exactly what he has in mind.

Orioles Chief Operating Officer Greg Bader offered a little glimpse during a talk before a Baltimore business crowd earlier this week.

“Imagine what we’re going to do when we have a complex that can have more concerts and more festivals and then add on top of that a 365-days-a-year experience, live-work-play, that works so well in so many other major league sports towns, where you can have retail, you can have hotel, you can have residential, you can have entertainment all within a few blocks,” he said. “And kind of use the Camden Yards complex as a bookend to what’s happening and going to happen at the harbor.”

Does that mean more dining and drinking options? Could there be condos in the B&O Warehouse? We’ll have to wait and see.

Some have pointed to ballparks like the Texas Rangers’ suburban Globe Life Field, which has an adjacent Texas Live! dining, entertainment and concert area from Baltimore-based Cordish Companies. (Disclosure: Cordish is The Banner’s landlord.) Baltimore Orioles fans who talked to Banner columnist Kyle Goon gave mixed opinions on whether they’d want something similar at Camden Yards.

Earlier this year, Angelos and Moore toured suburban Atlanta’s Truist Park, home of the Braves. The surrounding area is known as the Battery, including a concert venue, shops and restaurants.

It seems likely that the Orioles would bring in a development company as a partner on the project, but we’ve yet to hear any details.

Also in question is the legal authority for the state to grant exclusive use of that land to the Orioles for nonsports development, without offering a chance for other developers to make a bid for it.

And when it comes to development, how exactly would the approval process work? The MOU says broadly that “State/MSA will have approval rights over development plans,” but doesn’t spell out the details of the approval process.

How will the state ensure the Orioles keep up on their new operations and maintenance responsibilities?

Under the proposal, responsibility for day-to-day operations and maintenance of the ballpark would shift from the Maryland Stadium Authority to the Orioles. In exchange, the Orioles will pay no regular rent to the state for the stadium, as they do under their current, about-to-expire lease.

The arrangement is similar to one in place for the Baltimore Ravens NFL team at neighboring M&T Bank Stadium.

What if the Orioles don’t keep up on their end of the bargain, and the ballpark falls into disrepair? It’s likely that the state will have some level of oversight, but the details aren’t spelled out yet.

The Ravens lease includes a requirement that the team designate employees to coordinate operations and maintenance with the stadium authority. The team and the authority must mutually agree on an operations and maintenance plan and budget each year.

How much money is involved in the deal?

The Orioles would not pay any regular rent to use the ballpark under the proposed deal. But there are other pots of money that flow back and forth between the team and the state.

The biggest amount of money involved is $600 million worth of taxpayer-financed bonds that the state would be able to issue for ballpark upgrades — more on that later.

For the 99-year ground lease, the Orioles would pay the state $94 million over the course of the lease.

The Maryland Stadium Authority currently spends $6.5 million each year on ballpark maintenance beyond the rent it has received from the Orioles, and $3.3 million of its savings on maintenance under the new agreement would be put into a new “safety and repair fund” that the Orioles can use.

The state also would create a “capital improvements and repair” fund with an initial $5 million, plus $1 million per year after that. “Money held in such fund will be available to pay the costs of capital works and emergency repairs,” according to the MOU.

On top of that, there would be a $10 million “emergency reserve fund” for emergency repairs, initially funded with $5 million from the state and $1 million from the Orioles annually for five years.

There’s also the matter of the left field wall. Fans will remember that the Orioles spent $3.5 million to move the left field wall back and build it higher ahead of the 2022 season, in hopes of decreasing home runs and making the park more pitcher-friendly.

After spending that money up front, the Orioles got the state to agree to discount the team’s rent going forward. The team was allowed to deduct one-fifth of the cost ($700,000) from their 2022 rent and again for their 2023 rent.

The MOU states that the Orioles “will continue to receive a credit for any unreimbursed Total Project Cost” of the “Left Field Project,” but it doesn’t specify how that would work when the team is no longer paying a direct rent.

How would $600 million worth of taxpayer-financed bonds be used for the stadium?

Once a new lease is finalized, it unlocks access to $600 million worth of bonds for stadium upgrades.

State lawmakers approved the money — and an identical amount for the Ravens — in 2022, both contingent on new leases.

The Ravens, working with the stadium authority, have started the process to tap the money and make improvements, after signing a new lease at the beginning of 2023. The Ravens have initially asked to use about $450 million of the $600 million available in state money.

The Orioles haven’t said yet how they might want to spend their $600 million.

Will the Orioles sell naming rights to the ballpark or field?

The Orioles have had the ability to sell naming rights to all or part of the park since 2001, but they’ve declined to do so. Could they do so now as part of a revamp and rebrand of the iconic stadium?

Naming rights are allowed so long as the name is not obscene, against the law or “antithetical to the character of the Ballpark as a prominent symbol of the State of Maryland.”

How could the Baltimore Ravens lease change?

There is a parity clause in the Ravens lease for neighboring M&T Bank Stadium, noting that each team should get the same amount of state-financed bonds.

But the Ravens lease also notes that if the state changes its agreements with the Orioles “in a manner that provides the Orioles with more favorable terms than those provided to the Team” — meaning the Ravens — then the state “shall modify its agreement with the Team to provide comparable terms to the Team.”

Given that the Orioles will have a crack at taking on a significant off-the-field redevelopment project that could be profitable, will the Ravens seek the same? So far the NFL team has stayed quiet about the Orioles lease.

How will there be ‘winners off the field’ in this deal?

Moore has repeatedly said he wants an Orioles lease deal to create winners both on and off the field in the community. He called this “a defining moment” for Baltimore during a public meeting earlier this month.

“Shame on us if we miss the opportunity to partner with one of our city’s crown jewels, the Baltimore Orioles, and not reimagine how we can work together to actually shape the city’s future,” Moore said.

The MOU is silent on any direct benefits to surrounding neighborhoods or Baltimore’s city government, like required community investments. Sometimes developers agree to make donations to neighborhood associations or to include a certain percentage of affordable housing units in the project. In Baltimore, establishments serving alcohol often strike agreements with neighbors on issues such as security and hours of operation.

In Milwaukee, for example, a new stadium deal for the Brewers includes a requirement that the team pay $40,000 annually to local youth sports organizations, an increase from $20,000 in the prior deal.

It’s not known yet whether there will be any sweeteners like that included in the future lease or a future development deal.

It’s likely that a revitalized stadium and additional development could result in more jobs and economic activity, but there haven’t yet been any projections. It’s not clear how much tax money could come into city or state coffers from a new project.