WASHINGTON INFORMER: Over the past few years, Pastor Brandon Enoch Bey has augmented the Black history instruction his children receive in D.C. public and public charter schools.

For instance, his curriculum highlights Maroon culture, the achievements of Madame C.J. Walker and Black Wall Street, the Harlem Renaissance, and D.C. history, including U Street. Most recently, he added books written by Nkechi Taifa, a native Washingtonian, Pan-African attorney and staunch proponent of reparations, to his home library.

Even with recent updates to the District’s social studies standards, Bey expressed concerns about the District’s ability to preserve its unique Black culture. He told The Informer that, with the influx of transients and changes to the names of neighborhoods, Black people’s contributions to the nation’s capital are being pushed farther into the margins.

That’s why, for Bey, curtailing youth delinquency requires the comprehensive protection of the District’s cultural heritage. He also touted the benefits of instilling pride in D.C. children about their culture, and the ancestors who engaged in commerce and cultivated traditions, starting from Africa.

“If we don’t push for Black history to be highlighted, then we’re just existing and not thriving,” said Bey, a Northeast resident, as he mentioned the Kush empire and Moors, what he called reflections of Black people’s social impact across the globe.

“Our history should be at the forefront,” Bey continued. “There are areas [of historical knowledge] that are vital for children to know their self-worth. The schools won’t touch on them and are even removing them from the curriculum, so it’s the parents’ job to invest in the next generation.”

Preparing Teachers for the Road Ahead

The social studies standards that the State Board of Education (SBOE) approved earlier this year will be implemented during the 2024-2025 academic year. For three years, the D.C. SBOE, community members, teachers, and social studies experts weighed in on the components of the standards.

The standards focus on time periods throughout American and world history. In elementary school, students will learn about ancient civilizations, the First Nations preceding the United States’ founding, and the foundations of modern society.

Middle school students will explore world geography and American history up until the Reconstruction Era. In the eighth grade, students will be able to participate in activities intended to increase their civic engagement.

Meanwhile, high school students will have more opportunities for historical and social science-based analysis through the exploration of global history, U.S. history, and D.C. history, the aspects of which focus on the self-determination of marginalized groups.

In preparation for this crucial milestone, the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) has been helping public and public charter school teachers develop expertise in teaching their students media literacy and the inquiry-based model of social studies. The agency has also been developing curricular material intended to encourage students to ask questions about informational and historical texts — specifically how people’s biases shape what they know about the world and their interpretation of major historical events.

This summer, OSSE conducted professional development sessions for a dozen teachers that centered on elementary-level historical inquiry and online information media literacy for students. Participants came out of those sessions with some understanding about how to help students think critically about the past and evaluate the credibility of information they find online.

OSSE will expand these efforts over the years. In the spirit of building capacity, the agency will also provide individualized professional development sessions at District public and public charter schools.

“In a society where young people have access to vast sources of information at the tips of their fingers, it is more vital than ever that they can sort fact from fiction online and understand how to search for and evaluate information,” said State Superintendent Dr. Christina Grant. “The new social studies standards include a focus on media literacy for all students in grades K-12, so we can build capacity in our young people to navigate this new information-rich era.”

An upcoming professional development session for teachers this school year that’s scheduled for Sept. 27 will focus more on the inquiry-based model of social studies instruction for high school students.

Madison Kantzer, OSSE’s social studies instructional systems specialist, said that participants will acquire the tools to help students further examine what she described as the limitations of understanding the history of marginalized groups when it’s told from the perspectives of colonizers.

“Professional development is part of a multilayered approach,” Kantzer said. “We’re supporting teachers with pedological support and curricular development opportunities to shift classroom instruction to historical inquiry. The feedback we get is positive. Teachers are excited to do these skills with students, and they see the urgency.”

The Greater Battle to Uphold Black History

In the latest juncture of the fight to preserve the integrity of social studies instruction, the Tennessee Teachers Association has filed a lawsuit against a two-year-old law that imposes restrictions on classroom instruction about race, gender and bias. Meanwhile, at least six schools in Arkansas opted to offer local credit for Advanced Placement African-American studies in the aftermath of the Arkansas Department of Education dropping the course.

In Florida, hundreds of Black churches have stepped up to teach Black history amid Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ efforts to dilute the history curriculum in deference to Floridians with racist, conversative sentiments. Elders in the District have taken similar steps, entering the classroom as substitute teachers to tell students stories about their life during the civil rights era.

As D.C. resident Tenika Mceachin’s two children continue to matriculate through middle school, she remains adamant about ensuring that Black history counts as a significant portion of what they learn.

That’s why Mceachin expressed satisfaction with D.C. Prep, a public charter network where she said her children could learn about Black history year-round, not only in February. She said it has become a matter of boosting her children’s self-esteem and helping them understand the totality of Black people’s contributions to the United States.

“I want my children to know that Black people are more superior than what people might think,” Mceachin told The Informer. “Some people think Black people aren’t relevant when in fact we are the most relevant. Black history would help us stand together [so] we would stop killing each other.”

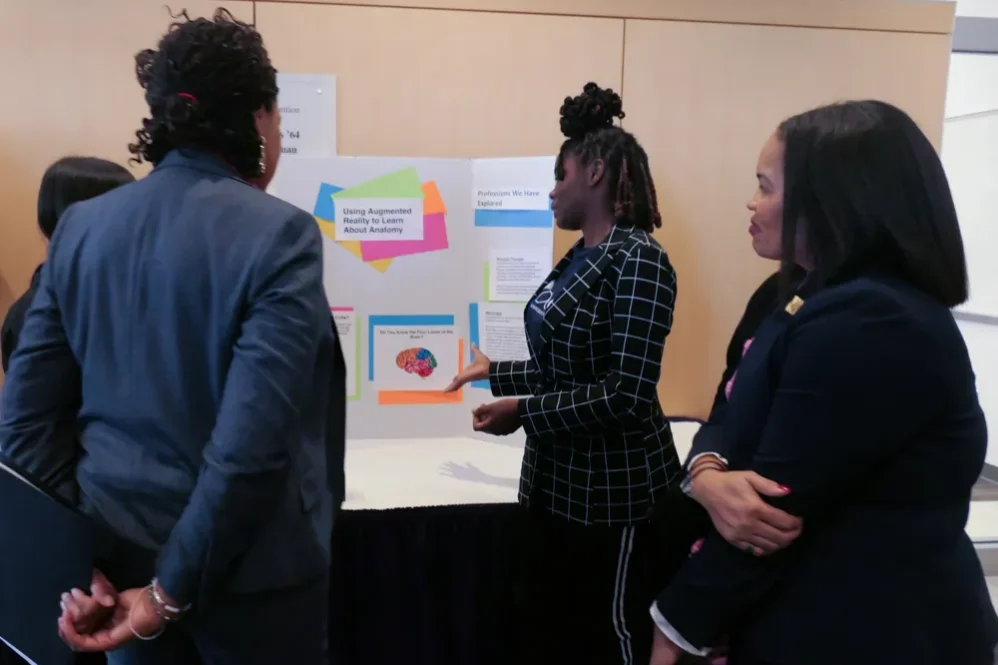

Photo: Zaicoria McLean (center), a 9th grader at Bell Multicultural High School, presents a project she worked on with Laylah Malloy and Teresa Jimenez, 11th graders at Jackson Reed High School, to D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser (left) and Office of the State Superintendent of Education Christina Grant (right) at the District’s Advanced Technical Center at Trinity Washington University in Northeast on Nov. 14. (Shevry Lassiter/The Washington Informer)