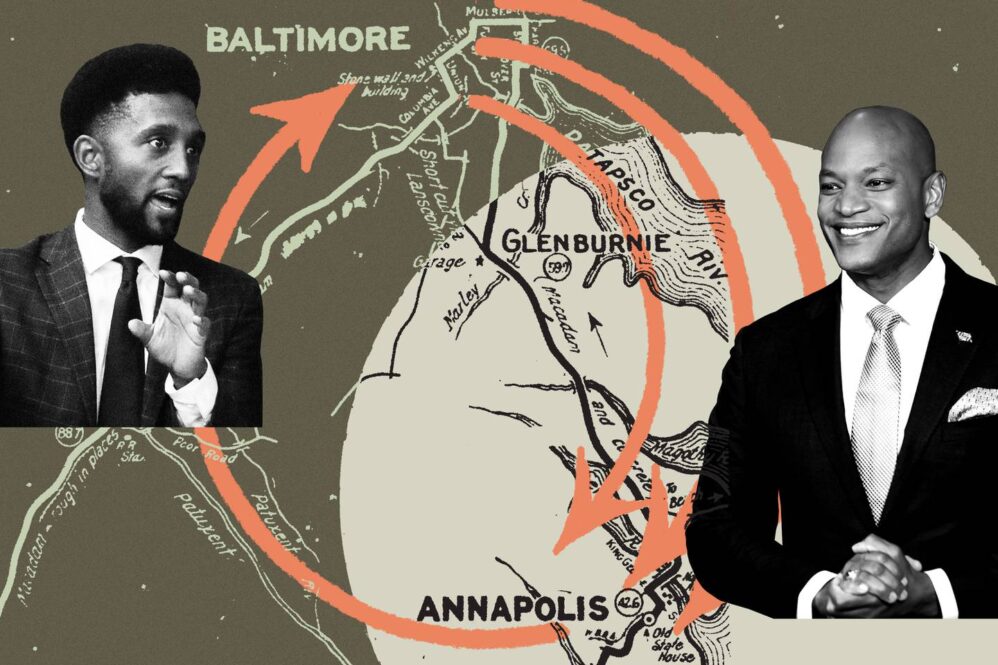

BALTIMORE BANNER: As Gov. Larry Hogan and Wes Moore prepare to swap places in the governor’s mansion, Baltimore officials and political analysts are gearing up for a leader they think will seek greater partnership with a city left in the lurch the past eight years.

Moore, who will make history as Maryland’s first Black governor when he is inaugurated in January, sailed to victory in his race against Del. Dan Cox, a far-right Republican who trumpeted his endorsement from former President Donald Trump, in the race to succeed Hogan, who is term-limited.

Hogan has maintained a relatively high favorability rating among Democrats statewide, who make up the overwhelming majority of the city’s electorate, but most Baltimoreans probably won’t remember Hogan fondly, said Matthew Crenson, a professor emeritus at the Johns Hopkins University and author of “Baltimore: A Political History.”

Though the Republican attributed his wins to “a purple surfboard of support” throughout Maryland, he never captured a base of support in Baltimore: Less than one-third of city voters cast their ballots for Hogan in both the 2014 or 2018 elections.

While Hogan and the four Baltimore mayors he overlapped with during his tenure came together for some initiatives, such as relaunching the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council with Mayor Brandon Scott, the Republican often used the city as a political foil and sparred with city leaders.

Michael Ricci, a spokesman for Hogan, offered an extensive outline of Hogan’s actions and policies tied to Baltimore for this article. He pointed to funding $1.5 billion in public safety efforts and $1.2 billion in improvements for both Oriole Park at Camden Yards and M&T Bank Stadium.

“While we have encountered numerous instances of indifference over the course of four mayors and five police commissioners, no administration has been a more active partner in providing support and resources to the city of Baltimore,” he wrote in a statement.

The governor has nevertheless met all of the mayor’s public safety funding requests, including $6.5 million this year to fund BDP’s Warrant Apprehension Task Force, he said, adding that state police have begun patrolling I-83, a longtime request of city leaders.

Scott said Moore will be a “true partner” to the city, pointing to a slew of Hogan’s decisions he said were harmful to Baltimore, including vetoing a plan to bring more funding to Baltimore schools — a decision the General Assembly overrode.

Such actions often reflected “a certain kind of indifference” toward Baltimore, Crenson said.

“One thumb in the eye was closing the [Baltimore City Detention Center] and moving prisoners to sites far from Baltimore, without even discussing it with anybody in Baltimore,” he added.

Breaking News Alerts

Get notified of need-to-know

info from The Banner

Then there’s Hogan’s cancellation of the Red Line, a proposed 14.1-mile east-west rail system that remains a sore spot with city advocates who say the line would have connected transit-isolated neighborhoods to more jobs and sparked economic development.

The rail line, which city and state officials began working on in 2001, was slated to cost $2.9 billion. The federal government agreed to fund nearly a third of the costs. Hogan, then a newly elected governor, canceled the project during citywide unrest following Freddie Gray’s death from injuries suffered in police custody, calling it a “wasteful boondoggle.”

He returned nearly $900 million in federal funding and announced that some state funding earmarked for the Red Line would instead be spent on the Purple Line, which connects the suburbs of Montgomery County and Prince George’s County. He also announced that nearly $750 million of state money would go toward maintaining and expanding highways in predominantly white counties.

Another symbolic example of the state-city relationship? State Center. Hogan canceled plans to redevelop the aging government office complex at the edge of downtown, and the administration later announced they wanted to gift the property to the city — but with no commitments of state money for demolition, planning or new construction.

“For eight years, we had a governor with performative support for Baltimore,” said City Council President Nick Mosby.

The Democrat called Moore’s election a game changer. He called Project C.O.R.E., a joint city-state program that demolished thousands of vacant buildings to spur redevelopment, Hogan’s most visible partnership with Baltimore.

“It’s not just about tearing down houses, but making real plans to transform communities,” he said, citing Moore’s agenda for Baltimore, which lists the Red Line as a “core priority.”

Both Mosby and Scott said Moore will be far more likely to come to the table with city officials than his predecessor. Mosby’s greatest hope for the new governor’s administration is historic investment in city transportation — “It’s our Achilles heel for economic development in the city” — while Scott’s is having “a true partner in building public safety in Baltimore.”

Ricci noted that Hogan’s Red Line decision fulfilled a pledge the governor made during his campaign and that the governor expressed an openness to transit alternatives from city leaders.

“None came,” he wrote. The Hogan administration launched major transit investments for the city, including a new East-West Corridor Project program and committing $9 million to the redevelopment of Penn Station.

Crenson said Scott and Moore’s personalities appear to stand in contrast to each other, which may embolden their future collaboration.

“Brandon Scott is cautious, collegial. His solution to most problems is to appoint a commission,” he said. “Wes Moore, while we haven’t seen him in action yet, seems more forthright, energetic, more willing to take the initiative. We’ll have to see how those two styles match up.”

Since winning the election, Moore has promised to move fast once in office.

It may be that Scott is energized by having a friendly governor, Crenson said: “You ask for more.”

“It’s not just about tearing down houses, but making real plans to transform communities,” he said, citing Moore’s agenda for Baltimore, which lists the Red Line as a “core priority.”

Lester Davis served as a deputy chief of staff, communications director and head of government affairs under former Mayor Jack Young. Now a Vice President at CareFirst and chief of staff to the company’s CEO, he advised the Moore campaign. The working relationship between Annapolis and Baltimore will be markedly different, he said.

“We’re going to be able to work with a lot of different folks. I think Baltimore’s better days are ahead,” he said.

Who will do the work?

Though Moore positioned himself as the candidate most aligned with Baltimore in a crowded Democratic primary field, which included Tom Perez and Comptroller Peter Franchot, many City Hall Democrats didn’t publicly rally around him until he won their party’s nomination. Scott opted not to endorse anyone until after the primary. Council members Zeke Cohen and Eric Costello were two visible exceptions.

Cohen attributed his support to the governor-elect’s willingness to center the city: ”Wes understands that for Maryland to be successful, Baltimore has to be successful.”

That may entail bringing in talent from Baltimore to fill his administration. Working for Moore would be an appealing opportunity for politicos inside and adjacent to City Hall, Cohen said. The governor-elect’s profile has risen significantly since Election Day, with many national Democratic pundits touting his victory as one of the cycle’s most notable wins.

The Scott administration has experienced a steady trickle of cabinet-level departures over the last year.

One of the first high-profile departures, Tisha Edwards, left her $220,000-a-year position as executive director of the Mayor’s Office of Children & Family Success for Team Moore before he even won the primary, becoming the campaign’s the chief of staff in September 2021. Edwards and Moore are longtime friends; she previously served as CEO of BridgeEDU, Moore’s now-shuttered nonprofit that assisted first-generation college students. She has also served as chief of staff to former Mayor Catherine Pugh and interim CEO of Baltimore City Public Schools.

Edwards will be tasked with building up the Moore administration’s ranks: the governor-elect named her appointments secretary this week.

While there’s no shortage of city talent eager to join the Moore administration, the governor-elect will likely recruit some staff members from the state and national scenes, Davis said.

“Don’t sell Baltimore City Hall short,” he said. “It’s still a desirable place to be. You’ll always find folks who want to cut their teeth at the local level.”

For his part, Scott doesn’t expect any bolstered turnover thanks to a new resident in the governor’s mansion.

“It wasn’t that long ago that … folks in other places weren’t trying to hire people from Baltimore’s government because of the stigma and because of the quality,” he said. “We’re going to continue to work to make sure that we have the highest-quality team here, but also know that we have to support our governor in order to have the best results for us as a city.”