After what has been considered one of the most unprecedented years in recent history, school districts across the country find themselves struggling to fill summer school teaching positions.

Teachers in the D.C. public school system say they’re seeing similar trends as conversations about bonus pay for summer school instructors continue to circulate.

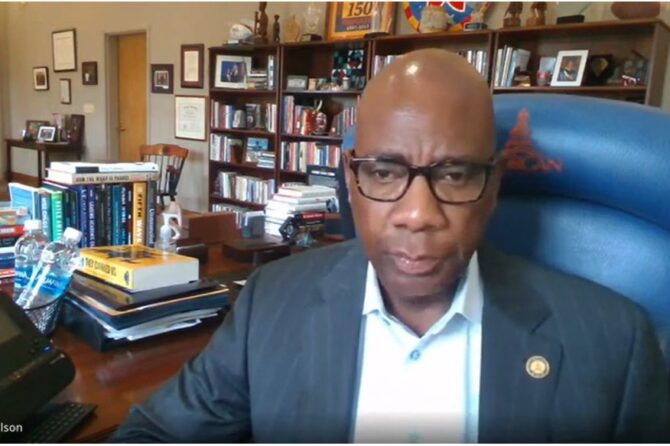

Washington Teachers’ Union President Jacqueline Pogue Lyons said the 2021-2022 school year took a toll on teachers who juggled responsibilities as instructors and COVID-19 mitigation specialists while tending to students’ socioemotional needs.

She said these and other challenges have led many teachers, particularly those with just a few years under their belts, to reexamine the benefits of working throughout the summer.

“When I was in that age range, I worked summer school to make ends meet but you need the emotional and psychological wherewithal,” Pogue Lyons said. “Our teachers have done a mighty job this year but they’re spent and they need this time to reflect.”

“Many of them are thinking about whether they’re going to stay to teach or transition to another system,” she added. “There’s a great need for teachers all over the country and it feels like the teacher pipeline is drying up.”

Shortly before spring break, data from the National Education Association showed that more than 50% of educators, age or years in the classroom notwithstanding, planned to leave the classroom earlier than expected because of burnout. Solutions to the problem that survey respondents suggested included salary increases.

This phenomenon, years in the making, comes after steady declines in both teacher salaries and the attainment of education degrees. In recent years, the attrition of teachers has become more pronounced among instructors with less than 10 years in the field as many have decided to explore other career options.

Over the last few months, DC Public Schools launched a campaign aimed at attracting new teachers through advertisements on buses and other public platforms. The effort counts as part of the Rigorous Instruction Supports Equity Initiative through which public school officials recruit teachers for 42 of the District’s highest-need schools along with performance-based incentives and support for new teachers.

Lawmakers in Maryland and Virginia have initiated similar attempts to battle a teacher shortage that has become more apparent as administrators attempt to secure educators for summer school.

In Maryland, options under consideration in some jurisdictions include bonus pay and reduction in class size. Meanwhile officials in Virginia have expanded employment opportunities to teachers with provisional licenses and those with nontraditional backgrounds.

In the District, public school summer programs begin July 5 and run through the beginning of August. At the elementary level, students can either engage in hands-on academic enrichment, strengthen their command of the English language, or participate in an extended school year program. The same applies at the middle and high school levels where students also have the opportunity to recover credits and participate in career academies.

This summer, first grade teacher Adam Severs said he plans to travel instead of teaching summer school. Last summer, he spent two weeks at Hyde-Addison Elementary School in Northwest helping first graders transition to second grade.

But with his school no longer serving as a site for summer instruction, Sever said he no longer feels compelled to return to the classroom in July, especially since he wants to recover from the 2021-2022 academic year.

When asked what would encourage him to change his mind, Severs counted smaller class sizes and a pay bump among his top wishes. Still, he pointed to situations he faced throughout the academic year when teacher and student COVID-related absences created situations that negatively affected student learning and further exhausted teachers.

“When you have staffing shortages and teachers out of the building, different adults have to cover classes,” Severs said. “While others may do their best, they may not be as qualified or experienced, [or] they may face larger class sizes. Students who need social and emotional learning in small-group settings don’t get those resources because staff members may be covering someone else. Things get diluted and the students and families we’re trying to serve [suffer].”

This article was written by the Washington Informer, read more articles like this here.